21st March 2019

A Question of Royalties

- A practical solution to taxing tech companies

A Question of Royalties

Tax avoidance and profit-shifting by multinational companies has been high up the economic policy agenda for a decade. Yet, despite an unprecedented global initiative1 and a series of loudly-trumpeted domestic measures to counter the problem2, TaxWatch’s first report3 recently estimated that what we called the “Tech 5” companies4 alone paid £1bn less UK tax than they would have if the UK share of their global profits corresponded to the UK share of their global sales.

In this paper, we propose a radical but achievable solution to the problem. Given the inclusion of a curiously watered-down version of the solution in Finance Act 2019 (which we have called “Google Tax III”)5, the government is clearly already aware of it but not, it would seem, of its full potential. We think its full potential could be realised simply by ensuring it prevented the likes of the Tech 5 from misusing a few of the UK’s double tax treaties (particularly that with Ireland) to avoid its effect.

UK Budget – 29 October 2018

In his Budget on 29 October 2018, the Chancellor, Phillip Hammond, announced two measures aimed specifically at the kind of avoidance in which the likes of the Tech 5, in particular, have indulged: the much-heralded “Digital Services Tax” (DST)6 (that, as we note below, might arguably be called Google Tax II) and the less-noticed extension of income tax to include “offshore receipts in respect of intangible property” (that, as noted above, we have called “Google Tax III”).

Each measure seems to seek to address precisely the kind of exaggerated divergence between the UK sales and UK profits of the likes of the Tech 5 that we highlighted in our first report – by imposing UK tax by reference to the UK sales of such companies in addition to the existing tax on their UK profits.

But, while the government forecasts that the measures will raise considerable amounts of revenue (between £600m-£750m a year between them), as we explain below, the evidence suggests that the government could raise billions of pounds a year from them (perhaps as much as £8bn). The measures required are similar to those it has taken. They simply require a bolder, though entirely legitimate, approach to the possibilities provided by the international tax system.

In this report, we firstly consider the two measures, explain why they are half-hearted (and, arguably, cosmetic) and how they allow Ireland (these days, probably the world’s foremost facilitator of corporate tax avoidance) to frustrate their effectiveness. We then show what the government could do if it genuinely had a mind to tackle the problem.

Digital Services Tax (DST)

According to the government7, the DST will be a 2% tax on revenues generated by providers of “social media platforms, search engines and online marketplaces” to the extent that such revenues are linked to “the participation of a UK user base”. So, while it will presumably apply to the search engine-providing Google (perhaps making it “Google Tax II”) and the social media platform-providing Facebook, it will not, presumably, apply to Apple’s hardware business, Microsoft or Cisco (none of whose businesses involve social media platforms, search engines or online marketplaces).

The government forecasts that the DST will raise £275m in its first year of effective operation (2020-21 since its introduction is delayed until April 2020) rising to £440m a year by 2023-248.

As a tax on turnover rather than income or profits, the DST falls outside internationally-agreed principles for dividing taxing rights between countries. As such, it faced immediate opposition from the US government9. The UK government itself made it clear that the DST is, in any event, merely temporary and will only apply “until an appropriate long-term solution is in place”10.

On 29 January 2019, the OECD published a policy note11 outlining the bare bones of a new approach to allocating taxing rights on international trading profits among sovereign states – explicitly to address the problems posed by the likes of the Tech 5. Although the note includes some interesting and potentially radical ideas, it is very vague and only time will tell whether it heralds the long-term solution the UK government has in mind.

Either way, notwithstanding the fanfare accompanying its introduction, it does not seem that the DST is likely to provide any kind of effective answer to the problems the government faces in tackling the likes of the Tech 5.

Offshore receipts in respect of intangible property (Google Tax III)

This measure extends the scope of income tax to include certain UK royalties that are arguably not currently within its scope – essentially those paid by non-UK companies to other non-UK companies in respect of intangible property (IP) relating to trademarks and brand names.12

Like the DST, the measure seeks to impose tax not so much by reference to the net UK profits of the likes of the Tech 5 but by reference to their UK sales. But, unlike the DST, it does not seek to do so through a turnover tax that falls outside internationally-agreed principles for dividing taxing rights between countries.

Rather, as an extension to income tax, this measure falls squarely within international tax principles by seeking to tax income– in this case, the internal royalties generated by the likes of the Tech 5 (to the extent that such royalties relate to UK sales).

Role of royalties in Tech 5 avoidance schemes

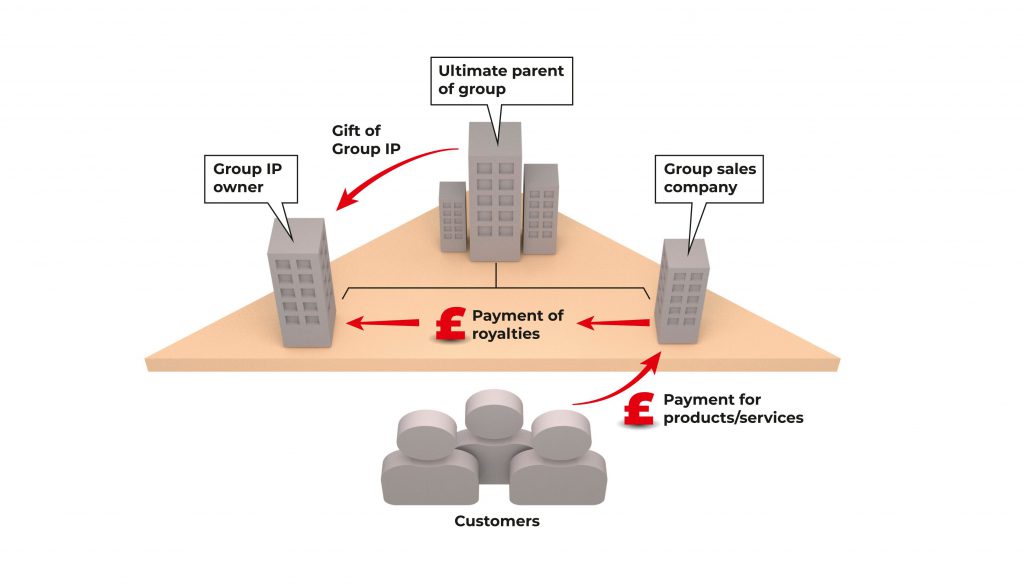

Royalties are fees paid to the owners of legally-protected IP by those who exploit such IP in their businesses. So, for example, radio stations are legally required to pay songwriters copyright royalties when they play their music on the radio.

Royalties are especially pertinent to the taxation of tech companies because they are at the heart of the tax avoidance we highlighted in our first report. As we explained, like many 21st century multinational groups, the Tech 5 have adopted a variety of counter-intuitive, tax-driven business models. Their basic premise is that, although the multinational makes its profits from selling its products and services around the world for more than it costs it to develop, make, market and sell them, most of the profits are attributable to various types of IP it has developed.

On this basis, the profits of the subsidiaries that sell the multinational’s products and services in, for example, the UK are reduced (often to little or nothing) by internal royalty payments they are required to make to fellow subsidiaries for the use of IP, in which its legal ownership has been artificially located.

A typical IP transfer pricing scheme

By artificially locating the intermediate legal ownership of the IP in avoidance-facilitating jurisdictions such as Ireland, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Switzerland, the multinational can avoid UK tax on UK royalties. Even though such royalties are within the scope of UK income tax, the UK has agreed double tax treaties with these jurisdictions. Under these, only the avoidance facilitating country may tax them.

By artificially locating the ultimate legal ownership of the IP in a tax haven like Bermuda, the multinational can avoid tax on the UK royalties in the avoidance-facilitating jurisdictions because the profits of the subsidiaries receiving the intermediate royalties are, in turn, reduced or eliminated by royalty payments to the ultimate legal owner of the IP. The avoidance-facilitating jurisdictions of course do not seek to tax those royalties on their way to the place of ultimate ownership. Since Bermuda has no tax regime, none of the royalties is taxed anywhere.

Under these kinds of business models, most, if not all, of the multinational’s profits are said to belong not to the subsidiaries who develop or make or market or sell the group’s products and services, but to the tax haven-based subsidiaries in which the ultimate legal ownership of the IP has artificially been placed.

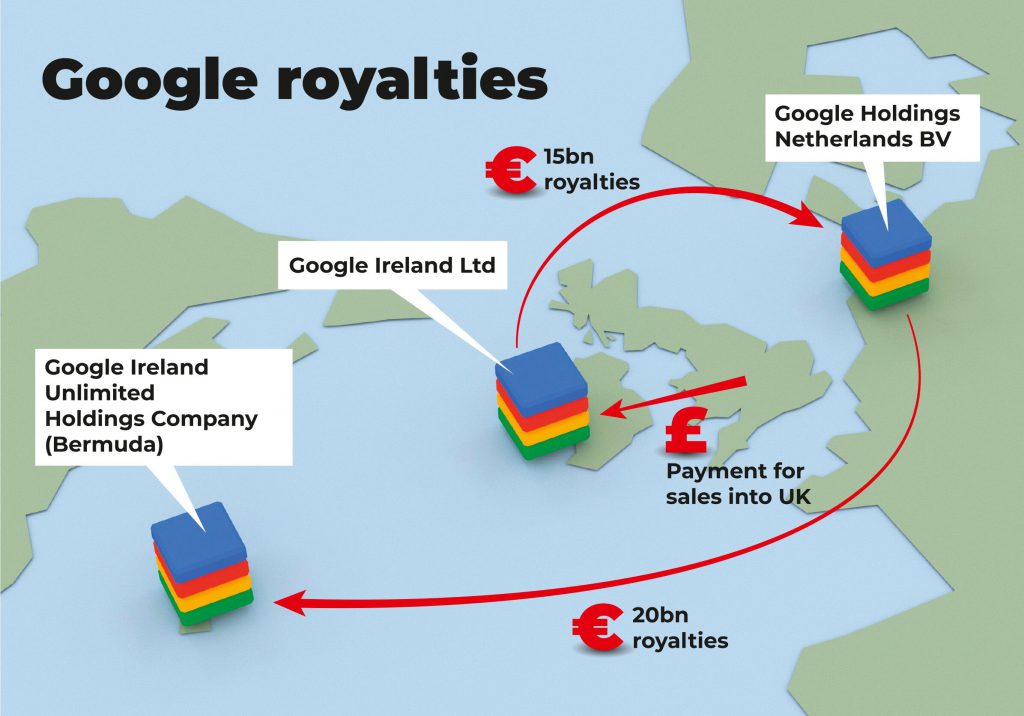

Taking Google as an example, nearly all its income comes from selling advertising space through a mixture of on-line “auctions” and old-fashioned salesmanship. In an effort to avoid UK tax on its profits from UK sales, the advertising is sold by an Irish subsidiary of Google13 which (arguably) has insufficient physical presence in the UK to be taxable here.

In any event, in line with the business model summarised above, the Irish subsidiary has little in the way of taxable profits because it is required to pay substantial royalties to a Dutch fellow subsidiary14. This, in turn, is required to pay equally substantial royalties to a Bermudan fellow subsidiary15.

The accounts of Google’s Bermudan subsidiary show that, in 2017, it received around $20bn in royalties from (undisclosed) fellow Google subsidiaries. Reuters recently reported16 that most (if not all) of these royalties were from its Dutch fellow subsidiary (whose 2017 accounts show that it, in turn, received nearly €15bn (around $13bn) in royalties from its Irish fellow subsidiary – along with a further €5bn (around $4.5bn) from a fellow subsidiary17 based in another avoidance-facilitating jurisdiction (Singapore)).

Google’s Royalty Payments from UK source

It is arguable both whether the vast majority of the profits of multinationals like the Tech 5 really is derived from IP and whether the royalties in relation to UK sales that are ultimately paid to Bermuda are outside the current scope of UK income tax. But most tax authorities seem to accept the premise of these business models and HMRC seems resigned to not taxing the royalties.

Taxing UK royalties

The proposed extension of income tax (Google Tax III?) seems, on its face, to be the UK government saying to the likes of the Tech 5: “OK, if you’re right that most of your profits are attributable to IP, we’ll tax the UK’s share of those profits by putting it beyond doubt that UK royalties paid in respect of such IP are liable to UK income tax”.

So, where, for example, Google’s Irish subsidiary sells advertising space to a UK customer in respect of which it is required to pay royalties to its fellow Dutch subsidiary which is, in turn, required to pay royalties to its fellow Bermudan subsidiary, there should, under Google Tax III, be an income tax charge on those UK royalties.

On the face of it, that should give rise to a substantial increase in UK tax. As noted above, Google’s Irish subsidiary (that not only sells Google’s advertising space in the UK but in the rest of Europe and in the Middle East and Africa (EMEA)) paid €15bn in royalties in 2017 to its Bermudan fellow subsidiary.

Given Google’s lack of transparency, it’s not possible to say with any precision how much of that €15bn was in respect of UK royalties. But Google’s public filings in the US suggest that around 27% of Google’s EMEA sales are UK sales18. If UK royalties were similarly around 27% of the royalties paid by Google Ireland Ltd via Google Holdings Netherlands BV to Google Ireland Holdings Unlimited Company in Bermuda, it would suggest that, in 2017, around €4bn (around £3.5bn) was paid in UK royalties.

With UK income tax at 20%, that would suggest that Google Tax III could potentially raise £700m a year from Google alone, which, in turn, would suggest that it could potentially raise around £2bn a year from the Tech 519 and anything up to £8bn a year overall20. Yet the government forecasts that Google Tax III will raise only £475m in total in its first year of application (2020/21) – and to dwindle to only £165m a year by 2023/2421.

It seems odd that the government estimates that a measure that, on its face, would seem to be capable of raising anything up to £8bn a year, will not only raise a considerably lower amount in its first year of application but will dwindle dramatically thereafter.

Either this is yet another Google Tax that doesn’t tax Google ( because, for example, it has been drafted in such a way that it does not include royalties paid by the likes of the Tech 5) or it anticipates that they (and other multinational groups) will take increasingly successful steps to try to avoid the effect of the measure. It also evidently has no plans to effectively counter such steps.

Treaty shopping

It is to be hoped that the government has learned from its mistakes with Google Tax I and has ensured that Google Tax III has been drafted in such a way that it includes royalties paid by the likes of the Tech 5. There are some fairly widely-drawn exemptions that could possibly be exploited by the likes of the Tech 5 but the most likely way in which Google and others will seek to avoid the effect of Google Tax III is through some kind of “treaty shopping” scheme.

As noted above, bilateral double tax treaties form an integral part of the avoidance schemes employed by the likes of the Tech 5. The UK (in common with the other main countries in which these multinationals operate) has made bilateral double tax treaties with its trading partners under which, to avoid double taxation, they mutually cede to each other their right to tax income such as royalties where they arise within their territories to residents of their treaty partners.

So, for example, although Google Tax III will put it beyond doubt that the part of the royalties paid by Google Ireland Ltd to Google Holdings Netherlands BV that relates to UK sales is liable to UK tax, the double tax treaty between the UK and the Netherlands provides that only the Netherlands may actually tax them.

On the other hand, there is no double tax treaty between the UK and Bermuda so, unless Google takes steps to avoid its effect, Google Tax III should ensure that the UK is able to tax that part of the royalties paid by Google Holdings Netherlands BV to Google Ireland Holdings Unlimited Company in Bermuda that relates to UK sales.

The government understandably thinks that groups like Google will try to take steps to ensure they do not have to pay UK tax on their UK royalties. The most likely means would probably involve restructuring operations such that UK royalties are paid only to subsidiaries resident in countries with which the UK has made a double tax treaty under which only the UK’s treaty partner may tax such UK royalties. The selection of countries through which to route transactions in this way is colloquially known as “treaty shopping”.

Google could, for example, simply make its Irish-registered, Bermudan-based subsidiary, Google Ireland Holdings Unlimited Company, tax resident in Ireland (as Irish law will shortly require it to do in any event). The UK has a double tax treaty with Ireland under which only Ireland may tax UK royalties paid to Irish residents so, unless the UK took action to ensure Google Tax III applies notwithstanding the UK/Ireland double tax treaty, it would not apply to any of Google’s UK royalties.

Ireland

This would be especially attractive to Google given that, in 2009, the Irish government introduced a new tax regime for IP22 (which it further enhanced in 201423). This may well afford the Tech 5 and other many or all of the tax advantages they enjoy through the use of Bermudan subsidiaries, without the hassle of having to devise structures to cater for the inconvenience of Bermuda having no double tax treaties.

Successive Irish governments have a long history of actively facilitating this kind of international corporate tax avoidance with specially-designed measures like these. From the “Double Irish” to the “Single Malt” through myriad other iterations, Ireland has been at the forefront of facilitating eye-watering amounts of tax avoidance over the last 40-50 years.

Given the lack of transparency involved, it is impossible to be precise about figures but it is undisputed that, over the years, the Irish Government has actively enabled multinational groups to avoid many, many billions of dollars in tax (tax that, without Ireland’s active facilitation, would largely have been paid to its fellow European Union partner states). And, of course, the Irish Government has recently been forced by the European Commission (the EC) to demand more than €14bn in back taxes from Apple to whom, the EC say, the Irish Government gave illegal State Aid24.

So many multinationals moved their IP to Ireland in 2015 (presumably to take advantage of the enhancement to the regime) that Ireland’s GDP increased by more than a third25. While in most countries royalty payments account for less than 1% of their GDP, for Ireland it has exceeded 20% in recent years26.

Apple seems to have been one of those multinationals that has already restructured its avoidance schemes to take advantage of the latest tax avoidance facilitation offered by the Irish government27. Others in the Tech 5 may well have since followed suit – especially as the UK government gave warning in December 201728 of its plans to tax these kinds of royalties and that those paid to companies resident in countries with which the UK had a double tax treaty would be excluded.

Applying the measure despite a double tax treaty

The government seems to have anticipated the possibility of treaty shopping since it has included an anti-treaty shopping clause29 that provides that, where there is a certain kind of treaty shopping, Google Tax III will apply despite anything in a double tax treaty. But the fact that the government nonetheless forecasts that the measure will raise only £475m in its first year of operation and dwindle dramatically thereafter suggests that the likes of the Tech 5 will be free to use other types of treaty shopping to avoid Google Tax III.

Given that the measure is presumably aimed at the very tax avoidance that sparked the OECD’s BEPS project and given the sheer scale of the amount of tax being avoided, it is hard to understand why the government would make only superficial attempts to ensure Google Tax III works effectively.

The government did make it clear in the consultation document that it issued in December 2017 that it “intends to respect all of its international obligations in the application of the measure”30. It did not specify what it meant by its “international obligations” but the context suggests that it had in mind the 100+ double tax treaties it has made with other countries31.

It is unclear why the government considers that including a partially effective anti-treaty-shopping clause within Google Tax III would fulfill its international obligations while including a fully effective one would somehow contravene them. But all the evidence suggests that the UK’s “international obligations” do not prevent it from taxing these kinds of UK royalties.

While the UK has made many treaties in which it has ostensibly ceded to its treaty partners its right to tax UK royalties, it does not follow that it is precluded from taxing them where, as is so clearly the case with the likes of the Tech 5, the royalties are a fundamental aspect of tax avoidance structure. The main purpose of Double Taxation Treaties is to avoid double taxation.

Tax treaties are not designed to facilitate the avoidance of taxation – notwithstanding their persistent use by a small number of governments (the Irish in particular) to do precisely that. Most of the UK’s treaties are based on the OECD Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital, the Commentary to which makes it clear that, in light of their clear purpose, governments are perfectly entitled to ensure that any anti-avoidance legislation they enact applies notwithstanding the terms of a treaty – especially if the avoidance at which it is aimed involves the misuse of the treaty32.

One of the main action points of the OECD’s BEPS project was to prevent the misuse of tax treaties. Action Point 6 (Treaty Abuse) suggests the inclusion of a general anti-abuse provision in all double tax treaties.33

Google Tax III is clearly anti-avoidance legislation and the avoidance at which it is aimed equally clearly involves the use (or misuse) of certain treaties. Given the clear purpose of tax treaties and the unequivocal support of the OECD Commentary and the BEPS project, it is unclear why the UK government thinks taxing UK royalties of companies involved in avoidance and misuse of a tax treaty (in particular that with Ireland) would contravene the UK’s international obligations.

Applying any legislation that is in tension with the specific provisions of an international treaty is (and should be) rare. But now would seem to be the time and this would seem to be the issue when it would be fully justified– especially as, in practice, such action could be focused on the very small number of treaties where abuse is taking place.

Previous cases of the UK applying anti-avoidance law despite a tax treaty

It is not as if there is no clear precedent for applying anti-avoidance legislation despite a tax treaty where it is deemed necessary in the national interest to do so. Indeed, when it was done in 2008 to counter an avoidance scheme involving considerably less tax than the Tech 5 alone are avoiding, the legislation34 was even drafted to deem that it had always applied (i.e. it had retrospective effect). Crucially, both the UK courts35 and the European Court of Human Rights36 deemed the measure to have been proportionate in the circumstances.

A quote from the ECHR’s decision in that case is perhaps pertinent here:

“The Court notes that in the present case the object of the legislative amendments in issue was to prevent the DTA tax relief provisions from being misused for a purpose different from their originally intended use, that is relieving taxpayers from double taxation. The Court considers that it is a legitimate and important aim of public policy in fiscal affairs that a DTA should do no more than relieve double taxation and should not be permitted to become an instrument by which persons residing in the United Kingdom avoid, or substantially reduce, the income tax that they would ordinarily pay on their income. Moreover, it is in the general interest of the community to prevent taxpayers resident in the United Kingdom from exploiting the DTA in a way which would enable them to substantially reduce their income tax and secure a competitive advantage over those who chose not to use such a scheme.”37

Given that the circumstances regarding the Tech 5 and their ilk are far more serious than those which the 2008 legislation sought to tackle, it is puzzling why the government seems to have chosen to take such a soft line.

Double taxation

It may be that the government is concerned that, if it applies the new legislation despite anything in one or more of its double tax treaties, royalties will end up being taxed both in the UK (where the royalties arise – the “source state”) and one of its treaty partners (where the company receiving the royalties is resident – the “residence state”).

Given the alacrity with which the world’s multinationals have moved their IP to Ireland over the last few years, it seems unlikely that they are required to pay any significant Irish tax on their royalties. But, if that is the government’s concern, there does not seem to be any reason why Google Tax III could not include some kind of provision under which any company that could prove that it had paid tax on its UK royalties in the country in which it is resident could claim a credit for any such tax against the UK tax it has to pay on those royalties.

Double tax treaties made under international tax principles often provide for taxing rights on certain items of income to be shared. Indeed, royalties are a prime example of such income under many treaties – with the residence state traditionally being responsible for relieving any double taxation that arises as a result of both countries taxing the same income.

UK law therefore already includes provisions enabling UK residents who have received income arising in other countries to claim credit against UK tax for any foreign tax they have paid there38. There does not seem to be any obvious reason why such provisions could not be adapted for inclusion in Google Tax III to provide for the UK as source state to take responsibility for relieving any double taxation that arises when Google Tax III is applied despite a double tax treaty.

In such circumstances, it would not seem to be all that difficult to devise rules to allow non-resident recipients of UK royalties to claim credit against UK tax for any foreign tax they have paid in the country in which they are resident.

Conclusion

The problems posed by the business models used by the likes of the Tech 5 are not easy to solve. The proposed Google Tax III is by no means the perfect solution but it seems to us to be the best attempt yet put forward.

But the self-imposed restrictions the government has attached to it ensure that it is no solution at all. If we are right that the reason the government estimates that so little tax will be raised by Google Tax III is that double tax treaties prevent the government raising any more, we would recommend that the government takes more effective steps to ensure that it applies when it should, despite any specific treaty provisions.

All the evidence suggests that the OECD, the UK courts and the European Court of Human Rights would all support such a move. The billions of pounds of tax at stake demand it.

Notes