26th October 2018

Corporate tax and technology companies

– still crazy after all these years

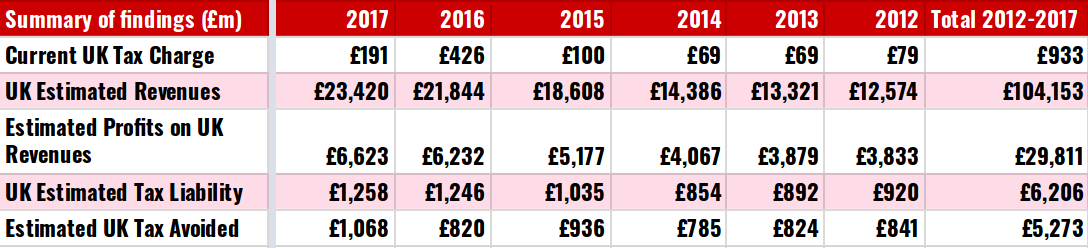

Despite a supposed international clampdown, the top 5 tech companies avoided an estimated £5bn UK tax in last five years

For the best part of ten years, there has been growing public concern about tax avoidance by multinational companies. The world’s largest tech companies have played a particularly important role in this story, becoming known as much for their prolific tax dodging as for their innovative products.

For many of these companies the European market is one of, if not the most, profitable market in the world. However, they structure their business to ensure that they pay very little tax on the profits they make in the UK and other European countries. The mechanism for achieving this is “profit shifting”: making profits disappear in profitable markets and moving them to a tax haven.

The tax strategies of large multinationals are well understood. Knowing just how much tax revenue is being lost is more difficult.

Profit shifting, especially when combined with the financial secrecy inherent to many tax havens, makes it very difficult for the public to see just how much profit multinationals are making in any given country and therefore how much tax they might reasonably be expected to pay.

In this paper we seek to estimate the revenues made by 5 of the largest technology companies in the world – the Tech 5 – from their UK customers. The companies included in the study are: Apple, Google, Facebook, Cisco Systems and Microsoft. We then estimate the profits these companies are making from their UK sales based on the published profit margins of those companies. From there we can make an estimate of how much tax these companies would generate in the absence of profit shifting.

In total we estimate that in 2017 these five companies earned revenues of £23.4 bn from UK customers. We further estimate that profit attributable to these sales was £6.6bn, which at the prevailing rates would have given a tax liability of £1.26bn.

The profits declared in the accounts of the UK subsidiaries of these companies, and their tax liabilities, were far less. In total, the accounts of the main UK subsidiaries of the companies we looked at suggested a combined tax liability of £191m. This is more than one billion pounds less than we calculate would have been due if the accounts of the UK subsidiaries of the Tech 5 more accurately reflected the revenues and profits made from UK customers.

These findings bring into focus just how much money the UK government is losing to profit shifting by large multinationals every year, and how efforts to combat this practice have largely failed. To put this into context, HMRC estimates that corporation tax avoidance by all large companies costs the Treasury just £700m a year.[1]

HMRC accepts that this form of tax avoidance, profit shifting, is not included in their analysis of the ‘Tax Gap’. The reasoning given by HMRC for this is that the issue is seen as the competence of the OECD and not HMRC alone and that it does not necessarily breach the letter of UK law, although, as is discussed below, there is a clear intent to change international rules to stop these practices. However, our findings reveal that profit shifting by the Tech 5 alone has a greater impact on revenues than all other tax avoidance practised by all other companies in the UK.

The table below sets out the total impact of tax avoidance by the Tech 5 between 2012 and 2017. A detailed breakdown of the results of each company is included within the report.

Background

Tech firms, it is argued, present a particular difficulty for tax authorities. The core of their business is not tangible, bricks and mortar operations, but the development of technology. The profits, they say, should mainly accrue not to the people selling their products or indeed to the programmers and developers who create that technology, (mainly based in California). They belong to whichever subsidiary of the company owns the relevant intellectual property, i.e. the trademarks, patents and other legally protected know-how that the company relies on to protect its technology. These intellectual property rights can be held by subsidiaries located in tax havens, which allows companies to claim that the majority of their profits are made in these tax haven subsidiaries.

Reaction and Reform

In the years following the global financial crash, and in the context of severe cuts to public spending, the digital giants provoked outrage when it was revealed just how little tax they were paying on their profits. In 2010, Google was revealed to be paying just 2.4% of its non-US profits in tax. [2]

In 2012, in response to the outcry that followed the headlines, the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) summoned representatives of three multinationals (Starbucks, Google and Amazon) to explain their tax policies.[3]

In the previous year (2011), Google’s UK subsidiary, Google UK Ltd had recorded revenues of £396 million but recorded a corporation tax charge of only £3.4 million.

Following pressure from politicians and the public to crack down on the aggressive tax practices of large multinationals, public authorities took action. HMRC opened investigations into Apple and Google resulting in these companies making limited settlements with HMRC. In 2015 Google paid £69m after a settlement following a tax audit for previous years. In 2016, two Apple subsidiaries between them paid £323m in taxes after large adjustments were made to their previous years’ tax bills.

At the same time as authorities took administrative action, there was political agreement to change the rules. In 2013, G8 leaders met at Loch Erne in Northern Ireland, and issued the following declaration:

“Countries should change rules that let companies shift their profits across borders to avoid taxes, and multinationals should report to tax authorities what tax they pay where.”[4]

As a result of this the OECD were commissioned to develop a set of recommendations as to how countries should change their tax rules to combat multinational tax avoidance.

The product of this was the OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting program (BEPS). BEPS is defined by the OECD as:

“Base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) refers to tax avoidance strategies that exploit gaps and mismatches in tax rules to artificially shift profits to low or no-tax locations.”[5]

Action point 1 of the BEPS process was aimed at taxing the digital economy. When the BEPS programme of proposed reforms was finally reached, action point 1 was the one area that countries could not find agreement on and action was delayed to a later date. Proposals are still being worked on today.

However, despite this failure to take action on the digital economy, some countries – including the UK – took unilateral action. In 2014 George Osborne announced the diverted profits tax, which became known as the “Google tax”. This proposed a punitive tax rate of 25% on any profits artificially moved out of the UK.

Have efforts to tax tech worked?

Our research looks at the tax payments of the Tech 5 over the last five years. We find that years of naming and shaming, tax investigations and efforts to change the tax system have largely failed.

We estimate that in 2017, the Tech 5 made revenues of £23.5bn from UK based customers, and profits of £6.6bn. This would have yielded a tax liability of £1.26bn at a statutory rate of tax of 19%.

Instead, the main UK subsidiaries of the Tech 5 recorded a tax charge of £191m in 2017, representing more than £1bn in tax avoided in just one year.

To put this into some perspective, BT – which incidentally runs the network of copper cables on which all of these companies rely – recorded a UK tax charge of £541m in their 2017 financial year, on a significantly lower revenue base of £17.8bn.

Over the whole 5 year period, we estimate that the UK profits of the tech five were £29.8bn, yielding a tax liability of £6.2bn. Over that period the main UK subsidiaries of the Tech 5 declared a UK tax charge of £933m. That leaves a Tech 5 tax gap of a little over £5bn.

Our research shows that there has been an increase in tax paid by UK based subsidiaries of the Tech 5. However, a large part of this increase has corresponded to the increase in profits generated by these companies, with a much smaller amount being attributed to action to prevent tax avoidance.

Statutory UK corporation tax rate on company profits

Tech 5 companies tax rate in 2017

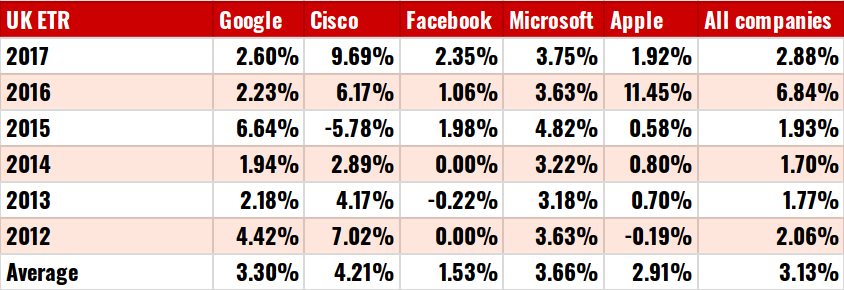

In total, the rate of tax paid by the Tech 5 on their estimated UK profit was 2.06% in 2012, rising to 2.88% in 2017. The statutory rate of tax on corporate profits in the UK is 19%.

In 2016 there was a small bump in the tax take, with effective rates on estimated UK profit reaching 6.84%. This was due to a large settlement between HMRC and Apple, which saw the company pay a substantial amount to settle underpayment in previous years.

Following these settlements, our research finds that there is only a limited change in tax behaviour by companies. To take the example of Apple, the company had an average effective tax rate on profits [attributable to UK sales] of 0.47% between 2012 and 2015. In 2016, due to a settlement which covered previous years, but was all accounted for in one year, the company paid 11.45% of its estimated 2016 UK profits in taxes. At the time the company announced that the action by HMRC would result in higher tax payments in the future also. In the 2017 annual reports of its UK subsidiaries, the company paid 1.92% of its estimated UK profits in taxes.[6]

A similar effect can be seen with Google, who reached a settlement with HMRC in 2015. Despite years of talk and supposed action by governments around the world to combat tax avoidance by multinationals, it is business as usual for the Tech 5.

How we did it

One of the perennial issues with reporting on the structures of large multinational companies is the opacity of their accounts. The way in which multinational companies structure their affairs means that accounts filed at national company registries (Companies House in the UK) rarely reflect the real revenues, costs and profits made in any given country. Often, revenues are booked to offshore subsidiaries and costs in the form of charges to other offshore subsidiaries are loaded onto UK-based subsidiaries. This reduces revenues, increases costs and decreases profits in the onshore subsidiary.

Consolidated parent company accounts rarely break down their financial figures by country, leaving no definitive, accurate, official account of the revenues and profits made by a company in any given country.

In this report we try to estimate the revenues and profits generated in the UK by 5 of the largest tech companies in the world. These estimates, by their very nature, will not be an exact reflection of the revenues and profits made by these companies. Until companies are forced to publish their accounts on a country by country basis the public will not ever be able to know these important details. However, we believe that our estimates present a much more accurate picture of the companies’ economic activity in the UK.

Our figures for revenues are based on a variety of sources. In some cases this data was available from the companies themselves. In other cases we had to look at revenues reported offshore, or make estimates based on market data. A description of how we estimated each set of figures is included below in our analysis of each company.

To estimate profits we then apply each company’s global pre-tax profit margin to our estimate of UK-based revenue. This introduces the assumption that the UK market is no more or less profitable than any other market.

This assumption of course seems to go against the grain of much thinking and practice in international corporate tax. Afterall, profit shifting relies on the idea that multinationals can make very different levels of profit in the different jurisdictions in which they operate. Multinational companies also will argue that the different functions of the company (e.g. sales, manufacturing, marketing, R&D) are spread across the world, and have different costs and profits associated with them.

The stated goal of the OECD reforms to the international tax system is to better align profits with where value is created. In the context of many companies attributing profits to shell companies which have little, if any economic activity, this principle may seem straightforward enough, however, even this is controversial, with no generally accepted definition of what constitutes value creation.

We believe that in the absence of more detailed data, using the average global profit margin of each company to estimate UK profits is a reasonable assumption for the purposes of this study.[7]

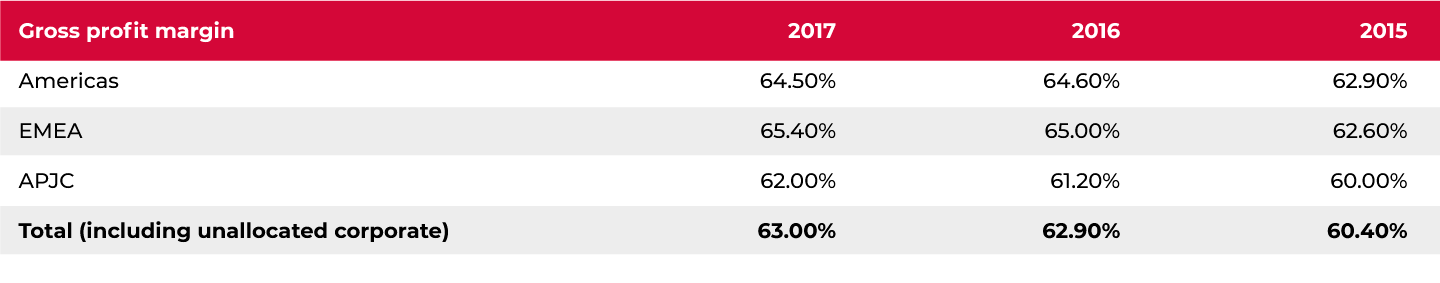

Cisco Systems reports gross profit margins by region in their US 10-k form. The gross profit margin is the profit made by the company excluding all the shared corporate expenses. It is the sales of the company, minus the direct cost of making and selling the product.

If we look at the 10-K form of Cisco System, we find that gross margins average 63% with the Europe, Middle East, and Africa region being at 65%.

As well as the direct cost of delivering a product or service, companies also incur indirect costs such as general administration and finance costs. For a multinational group of companies, it generally makes sense to centralise these costs – often in subsidiaries that are located geographically near the group’s corporate, administrative or financial headquarters.

The companies we look at in this study are all US-based. Their headquarters are all located in the US. This means that most of the group’s indirect costs tend to be incurred in the US.

This centralised approach does not distort the group’s global profit margin but, unless the group internally recharges such centralised costs to all the subsidiaries on whose behalf they are incurred, it may well distort the US and non-US profit margins respectively reported in the US parent company’s consolidated accounts. If there is no internal recharging of the centralised costs incurred in the US on behalf of the global group, their US profit margin may appear to be lower than it really is. The European margins will be higher.

The transfer pricing principles overseen by the OECD recognise this and, under the current tax rules of most major economies, the companies who incur these centralised costs are allowed to compute their tax liability as if they had recharged them to the other group companies on whose behalf they have been incurred, such that, for tax purposes at least, each relevant subsidiary shares the burden of the group’s centralised expenses.

This has the effect of equalising the group’s shared expenses across different regions. This supports our approach of using the global average profit margin to estimate UK profits.

After estimating the profit made on UK sales by the company, we then multiply that by the prevailing UK tax rate during the year under consideration to get a notional tax liability. We then compare this to the UK current tax charge as displayed in the main company accounts of the group’s UK subsidiary in order to produce an estimate of the amount of tax lost to the UK Treasury from profit shifting.[8]

Companies

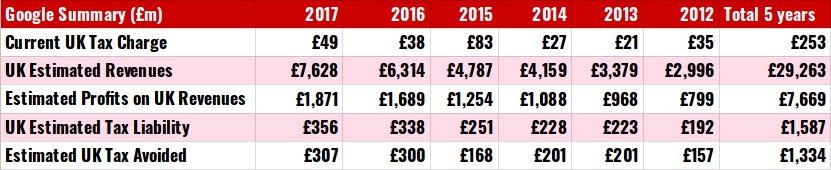

Until 2016 Google reported the revenues it made from the UK in its US 10-K filing. On average, around 9% of Google’s global revenues came from the UK between 2014 and 2016. We applied this average figure to Google’s 2017 global revenues to estimate the revenues generated from the UK in 2017.

Over the last 5 years Google has consistently made a profit margin of over 25% on all of its worldwide sales. In 2017, Alphabet, the parent company of Google reported profits of $27bn, on revenues of $111bn. The same profit margin applied to the UK revenues of Google would yield a profit of £1.8bn, and a tax bill of £356m.

Google UK had a tax charge of £49m in 2017.

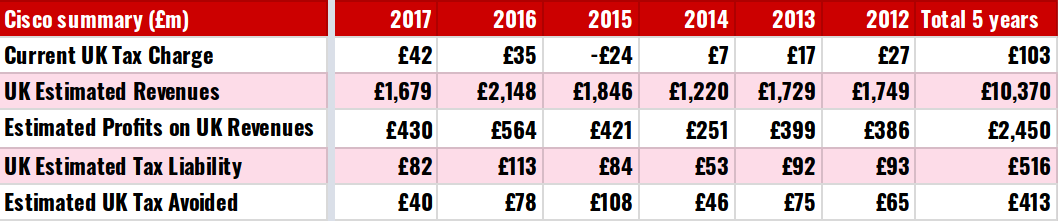

Cisco

Cisco Systems has a subsidiary based in the UK called Cisco Systems International Limited. It is responsible for the majority of Cisco’s sales in the Europe, Middle East and Africa region. Helpfully, the accounts of Cisco Systems International report separately on the revenues the company makes from UK sales, which were £1.6bn in 2017.[9]

Cisco systems made a profit margin of 25% in 2017 on all of its global sales. Applied to its UK sales this would yield a profit of £430m, and a tax bill of £82m. However, in 2017, Cisco International Limited and another UK subsidiary, Cisco Systems Limited, were charged £42m in tax between them.

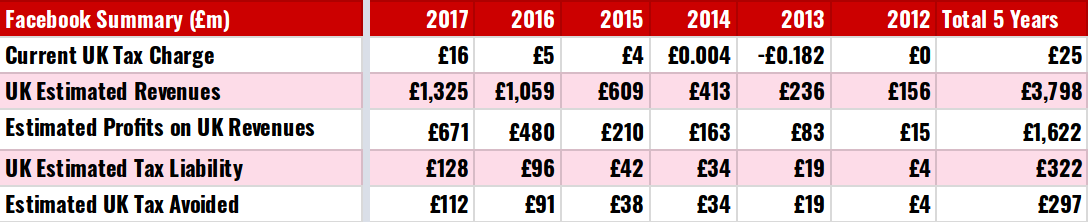

Facebook’s UK revenues were a little harder to estimate. Facebook’s global accounts do not break down their revenues by geography at all, whilst the accounts of the company’s UK subsidiary do not reflect the real UK revenues.

Until 2016, Facebook booked all of its UK revenue in a subsidiary in Ireland. Following public pressure about the company’s tax affairs, it started booking revenue from its largest customers through Facebook UK rather than an Irish subsidiary. However, smaller customers would still receive invoices from Ireland, meaning that Facebook UK’s accounts are not a true reflection of the revenue the company makes from UK customers.

In order to estimate Facebook’s real revenues in the UK, we looked at Facebook’s average revenue per user (APRU), which is published in a chart, broken down by region, appended to the company’s US stock market filings. We then took the mid-point between the US APRU and European APRU basing this calculation on the assumption that the UK would be at the top end of the European APRU range, but less than the US. Facebook’s userbase has been fairly stable at 32 million in the UK over the last five years. To get a estimate for UK revenue we then multiplied the APRU by 32 million.

When Facebook announced changes to its corporate structure, it was expected that the result would be that the company would pay millions more in UK taxes. Yet, although substantially more revenue was recognised in the UK accounts in 2016 and 2017, profits at Facebook UK did not increase in line with the increase in revenues.

In 2017, the company had a tax charge of £16m – substantially more than the £4m tax charge they recorded in 2015, but still a lot less than a company of this size and profitability might be expected to pay.

Our estimate based on how much Facebook makes per user, puts revenues in the region of £1.33bn in 2017 from UK customers.

Facebook is an immensely profitable company. In 2017, for each dollar the company generated in revenue, it made a profit of 50 cents. If we assume that the UK market is no less profitable than any other market the company operates in, then the company should have generated a profit of around £671m in 2017, as opposed to the £45.6m reported in Facebook’s UK accounts.

A profit of £671m would yield a tax charge of £127.5m. Facebook paid £16m in taxes in 2017 in the UK.

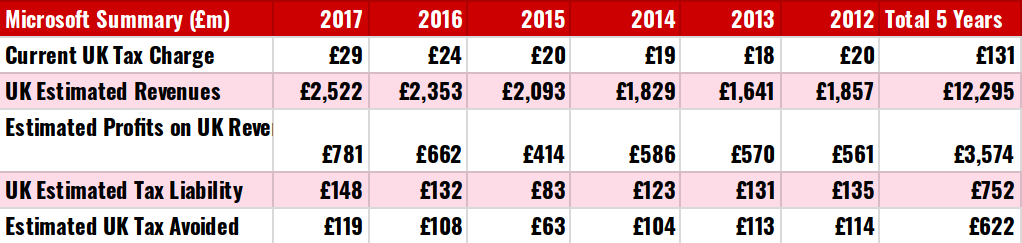

Microsoft

Microsoft’s UK accounts do not disclose any information about how much the company earns from UK customers. All of the revenue earned by Microsoft’s main UK subsidiary, Microsoft Limited, is income earned from other Microsoft subsidiaries.

Microsoft’s UK sales are booked by an Irish subsidiary, Microsoft Ireland Operations Limited. Its accounts provided a figure for revenues earned from the UK until 2015. Between 2013 and 2015 the proportion of the company’s global revenues that came from the UK ranged between 3.12% and 3.6%.

To estimate revenues that Microsoft gained from the UK in 2016 and 2017 we applied an average of 3.44% to the global revenue of Microsoft in those years.

Once again, we found that the amount of revenue that Microsoft earns from UK customers is far higher than that reported in the local accounts of Microsoft Limited. And again, the profit levels reported by the main UK subsidiary are much lower than Microsoft’s global reported profit levels. Overall, Microsoft made a pre-tax profit of 30% on its revenues in 2017, whereas Microsoft Limited, the UK subsidiary, reported a pre tax profit of under 10% of its revenues.

In total we estimate that Microsoft generated revenues of £2.5bn in 2017 from UK customers. This would yield an estimated profit of £781m and a tax bill of £148m in 2017. Microsoft Limited had a tax bill of £29m in 2017.

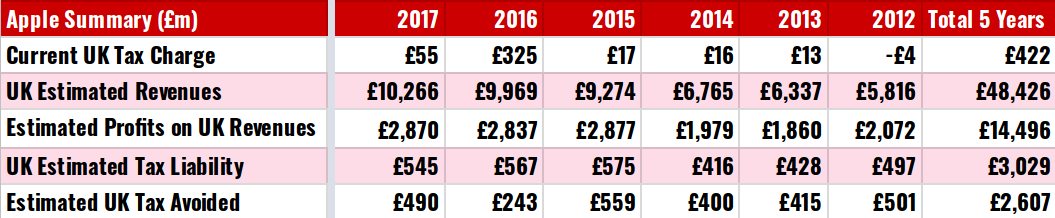

Apple

Apple is one of the most opaque of all of the companies we looked at, and so most difficult to analyse.

Apple has three principal subsidiaries in the UK: Apple (UK) Ltd, Apple Europe Ltd, and Apple Retail UK, Ltd. Between them they declared revenues of £1.5bn in the UK in 2017. This represents 3.75% of Apple’s European sales, according to the figure for European sales published in Apple’s global accounts, or less than 1% of global sales.

This is unrealistic, as the UK is one of the most important markets for Apple in Europe, and it seems implausible that Apple has a lower proportion of its sales in the UK than every other tech company in our study.

Some analysts have estimated that the UK market accounts for 10% of Apple’s global revenues. This would represent 42% of European sales. It may be that these estimates are too high. Certainly, Apple itself reports that no one market outside the US and China has accounted for more than 10% of sales in any of the past five years.

A better estimate of how much revenue Apple makes from the UK market might perhaps be derived from an estimate of the amount of money spent by UK customers on iPhones in the UK which was constructed from data on smart-phone penetration and market research. This shows that £6.3bn was spent on iPhones in the UK in 2017. This accounts for 6% of Apple’s global iPhone sales.

If we assume that other Apple products have a similar market share in the UK, then in 2017 Apple would have made revenues of £10.3bn in the UK. This is more than 6 times the amount reported in the accounts of the company’s UK subsidiaries.

Applying Apple’s global pre-tax profit margin of 28% to revenues of £10.3bn implies an estimated profit of £2.87bn and a tax bill of £545m. Apple’s three UK subsidiaries had an estimate tax charge of £55m in 2017 (see note 6). This would make Apple the biggest tax avoider of the companies we studied, responsible for £0.5bn of taxes avoided in just one year.

Notes

[1]See HMRC, “Measuring Tax Gaps 2018” p.20, available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/715742/HMRC-measuring-tax-gaps-2018.pdf

[2]Jesse Drucker, “Google 2.4% Rate Shows How $60bn is Lost to Tax Loopholes”, Bloomberg 21 October 2010, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2010-10-21/google-2-4-rate-shows-how-60-billion-u-s-revenue-lost-to-tax-loopholes

[3]Rajeev Syal, “Amazon, Google and Starbucks accused of Diverting UK Profits” The Guardian, 12 November 2012 https://www.theguardian.com/business/2012/nov/12/amazon-google-starbucks-diverting-uk-profits

[4]See: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/g8-lough-erne-declaration

[5]For more information on the BEPS project see:http://www.oecd.org/ctp/beps-frequentlyaskedquestions.htm

[6]Apple’s 2017 annual reports for 2 of its UK subsidiaries only covered half a year as Apple changed its accounting period. The 2017 figure for Apple’s tax charge is therefore an estimate. To get that estimate we doubled the tax charge of the two Apple subsidiaries that had only released half year reports. The result of this is that Apple’s tax charge figures should be read as covering a 5.5 year period.

[7]Some have suggested that a better way to allocate profits for tax purposes is to use a formula based on sales and the proportion of the company’s employees based in each country. This is to protect developing countries in particular, which are dependent on the extractive industries which see a large amount of product sales taking place outside the country. This is an interesting debate and not one which Taxwatch takes a position on in this paper. However, for the purposes of the particular companies which are the focus of this study, we believe that using an average pre-tax profit margin to estimate profits makes sense for the reasons that are set out.

[8] U.K. tax liabilities are computed by reference to many complex rules and commercial profits do not equate to taxable profits in any given year. However, most adjustments concern the timing of the taxation of profits. Taken over a period of time, commercial profits will be close to taxable ones.

[9]Throughout this report, figures given by companies in foreign currencies have been converted to pounds using the exchange rate on the day of the balance sheet.