How should profit be distributed within the modern multinational corporation? That is the key question at the heart of the debate on international tax avoidance, and one touched on by Taxwatch’s first report.

The aspiration of the OECD reforms to the international corporate tax system is to better align taxable profits to where value is created. However, what itself constitutes ‘value’ is a disputed concept, which is being discussed between international negotiators at this very moment. The UK government for example, feels that a significant amount of ‘value creation’ comes from the users of social media sites, which is the position they are currently taking in OECD negotiations.

Some argue that the “value” of products sold by large American technology companies is made in the United States, where the engineers and designers create the product. For that reason, under international tax rules profit is properly allocated to the US. The operations of these multinational companies in the UK are limited to less profitable activities such as sales and marketing. That is why so little profit shows up in the UK accounts of the subsidiaries of these companies and why so little tax is due. The scale of tax avoidance, they argue, is far lower than has been claimed, if it exists at all.

This is an argument which is shared by the corporate interests themselves.

Apple wrote to Taxwatch in advance of the publication of our first report to say that it is “indisputable” that the vast majority of the value of their products is created in the United States of America – and for that reason, most of the company’s tax bill arises in the United States of America.

This argument may appear logical – but does it correspond to the facts?

Current tax rules are not concerned with a measure of value, but with profits. Are US corporations allocating the profits of their business activities to the US, where all that design, product development and entrepreneurial innovation takes place?

No they are not. Indisputably.

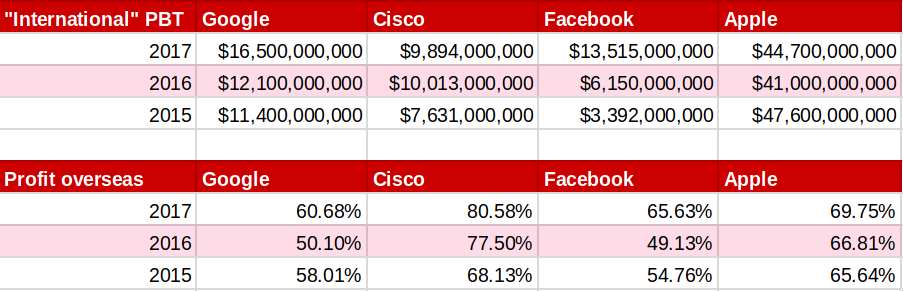

As part of their US corporate filings, Apple, Google, Cisco and Facebook all declare how much of their pre-tax profit they say is made overseas, and how much is made in the US. These figures appear as part of their tax note in order to help investors better understand their tax bill.

If you analyse those figures, you find that these companies are telling investors that the majority of their pre-tax (and post tax for that matter) profit is made outside the US.

In Apple’s case their US filings show that 70% of their pre-tax profit is made outside the US. In 2017, Cisco reported that a staggering 81% of their pre-tax profit was made overseas.

Below are two tables showing how much profit Google, Cisco, Facebook and Apple declared in their accounts as being earned outside the United States, and the percentage that number represents of their global pre-tax profit.

Why aren’t the profits in the US? It appears from the accounts that these companies are not recharging any of their group costs to their non-US subsidiaries, as they are entitled to do. The companies pay for all of their R&D costs, all of their product design, and all of their group administrative costs from their US revenues. This results in lower profit margins for the US business. Their overseas businesses, freed from any obligation to pay for the product design and innovation that are a significant part of the business, see their profits rocket (before zooming offshore).

Why are they set up like this? Probably because it is harder to avoid tax in the US, so why not get as much cost on the income statement as possible, and make all your profit overseas where those profits can be kept offshore and tax free.

Now all that is fine if the companies want to do that, but it then becomes very difficult to argue that these companies should face barely any tax charge in Europe.

After the publication of our first report, which sought to estimate how much profit was being made by 5 US tech companies from UK customers, and compared those estimates to the (very low) profits being declared in the accounts of their UK subsidiaries, there were some who criticised the report by arguing that the numbers we produced failed to recognise the reality of current tax rules, which rewarded the product designers and the innovators. The same argument of course made by Apple.

The irony of this argument is that the methodology in the Tax Watch report, which used the global average profit margins of companies, allocates more R&D and administrative costs to the European operations of Apple, Google, Microsoft, Cisco and Facebook than the companies themselves do!

The final question this raises is this. If these companies are not charging their European subsidiaries for R&D etc, and if they claim that the majority of their pre-tax profit is made outside the US, then how are they paying so little in Europe?

This confirms that most of the profit being made outside the US is being shifted towards tax havens. Indeed the companies themselves admit this. Microsoft’s 10-K contains the following statement:

Our foreign regional operating centres in Ireland, Singapore and Puerto Rico, which are taxed at rates lower than the U.S. rate, generated 87%, 76%, and 91% of our foreign income before tax in fiscal years 2018, 2017, and 2016, respectively.

Google say:

“Substantially all of the income from foreign operations was earned by an Irish subsidiary.”

Could it really be that he majority of the value of Google’s business is generated in Ireland? What on earth are all those people in California doing? Time for a restructuring perhaps?

What the accounts of these five tech companies confirm is what many of us of course already know. Companies arrange their affairs to move profit out of European countries and into tax havens, often though the use of royalties on intellectual property.

The perversity of this structure is that companies in our study are “paying” for the use of IP, but they are not paying it to the creators of the IP, but to another entity within the group – an entity which appears not to have incurred any significant costs for creating that IP in the first place. It is impossible to argue that this structure rewards the creators and the makers in any way (unless of course you count the creative lawyers and accountants who would have constructed such schemes).

How value creation is rewarded by the tax system is an important issue, and one which in the end will require a political rather than a technical answer. But when we have that debate, lets first start with an honest conversation about what is really going on.

Photo by Marvin Meyer on Unsplash