Mining the tax gap to pay for additional public spending pledges has become the norm during election campaigns for the UK’s major parties. This election cycle is proving to be no different.

Both Labour and Conservatives have cited around £6 billion as aspirational additional revenue to be gained per year from ‘tackling tax avoidance’ by the end of the next parliament. The Liberal Democrats have gone further, saying they will raise £7.2 billion in 2029-30, but don’t give the yield expectations in the intervening years.

Whilst there is more money to be collected from tackling the ‘tax gap’, as the latest figures show the sources of additional revenue may have little to do with tax avoidance.

It’s important to note that the tax gap is an estimate of total theoretical tax liabilities. HMRC use a variety of methodologies to measure the overall tax gap and provide an additional measure of ‘uncertainty’.

The manifesto pledges

An important part of tackling the tax gap is acknowledging that HMRC must have sufficient resources to fulfil its role. To this end, Labour has pledged to invest £555m per year in additional HMRC resources and the Lib Dems have pledged an additional £1 billion a year and are (understandably) expecting to get higher revenues in return.

The Conservatives have not pledged any additional funding, although they do plan to hire more HMRC staff, invest in Artificial Intelligence and focus on ‘problem issues’ such as umbrella companies and regulation of the tax advice market (which TaxWatch supports). As an unprotected department, unless additional resources are allocated to it under the upcoming spending review, HMRC would be subject to a real terms budget cut following the election. It is therefore hard to see how a future Conservative Government would achieve its ambition, as our analysis of their manifesto shows.

Prior to the election campaign Labour produced a 15 page document setting out in more detail how they plan to reduce the tax gap by increasing compliance activity, investing in technology and increasing ‘deterrents’ to avoidance and evasion through legal enforcement.

More than just avoidance…

It is evident from looking at the tax gap’s composition that trying to close it requires more than just focusing on reducing avoidance. Both main parties are to varying degrees guilty of conflating the tax gap solely with ‘tax avoidance’, which could be a deliberate ploy to engage with voters. It appears that both understand that the tax gap is made up of much more than tax avoidance, but the conflation is not helpful to understanding it, nor how best to reduce it.

As the latest figures show, it’s the smallest category by behaviour, accounting for less than 5% of the overall tax gap. Even if this is broadened out to include evasion and hidden economy (the two related types of behaviour) in total they account for less than a quarter of the total gap.

By far the largest source of underpaid tax is caused by errors and failure to take reasonable care, accounting for almost half of the total (Table 1).

Table 1. Tax Gap by behaviour

| Behaviour | Value (£bn) | % of Tax Gap |

| Error/Failure to take reasonable care | 17.8 | 44.72% |

| Evasion | 5.5 | 13.82% |

| Non-payment | 5.2 | 13.07% |

| Legal interpretation | 3.9 | 9.80% |

| Criminal attacks | 3.5 | 8.79% |

| Hidden economy | 2.2 | 5.53% |

| Avoidance | 1.8 | 4.52% |

| Total | 39.8 |

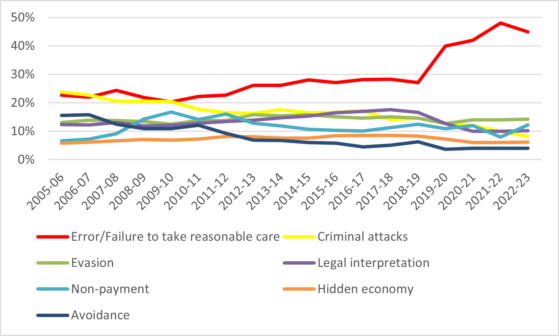

The proportion of the tax gap accounted for by error and failure to take reasonable care has increased over time. In 2005-06 it accounted for only 20%. While other sources, like evasion and the hidden economy, have remained largely stable, or declined, as have criminal attacks and avoidance, error and failure to take reasonable care rose gradually over time to account for 27% in 2018–19 before leaping to 40% in the following year (Figure 1).

The only other behaviour with a recent uptick is non-payment. Whilst this may be an anomaly, it will be interesting to see whether the proportion of the tax gap related to non-payment increases as other areas decrease. There is a danger that as other areas are addressed, a growing proportion of the additional revenue assessed as due moves from other behaviour categories into non-payment. Attempts to reduce the tax gap should therefore include provisions for collecting unpaid tax.

Figure 1. Tax gap over time by behaviour

Overall, attempts to reduce the tax gap must look to broaden the net to address the volume of errors and carelessness. This requires a different approach than that taken in relation to avoidance, which relies on a combination of legislative powers and compliance activity. Instead, errors and carelessness must be addressed by looking ‘upstream’ at potential issues before they become reporting errors or failures. This in turn requires a focus on ensuring that it is as easy as possible for taxpayers to get things right when completing tax returns, such as customer service support, successful automation of financial information and the clarity and ease of understanding the tax regime and guidance for taxpayers.

Not just the wealthy…

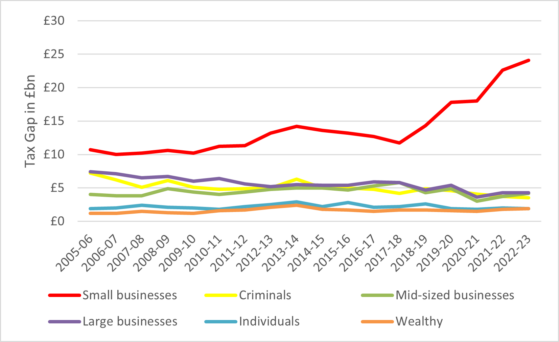

Drilling down into the data provided by HMRC it is also clear that targeting large corporations and the wealthy could not hope to raise the requisite £5bn per year, as much of the earlier wins in these categories have already been secured.

Whilst the tax gap for all other taxpayers is decreasing over time, the amount relating to small businesses is increasing, and now accounts for 60% of the tax gap, totalling £24bn in 2022-23. Examining changes over time, there is a notable increase in the tax gap for small business following the 2017-18 tax year (Figure 2). The increase is likely due to a combination of factors, which may include the use and abuse of R&D tax relief schemes and methodological changes with more random enquiry programmes picking up compliance issues.

Figure 2. Tax gap over time by taxpayer group

Looking upstream

Based on the tax gap data, it is clear that errors and failure to take reasonable care, especially by small businesses, should be addressed if the tax gap is to be reduced.

To their credit Labour acknowledges this. They cite previous work by TaxWatch on the allocation of resources required to improve tax collection, which demonstrated that the level of customer service currently provided by HMRC is not conducive to the effective collection of tax. Included in their plan to close the tax gap is a focus on upstream activities, with additional funds for improving HMRC’s digital services and a commitment to improve their core customer service offering.

Labour also recognises the proportion of the tax gap related to small businesses. This provides hope that should they win the upcoming election an incoming Labour government may address the tax gap from a slightly different perspective, improving customer service and taxpayers’ experience of HMRC.

Barking up the wrong magic money tree

The tax gap will continue to be mined by politicians keen to convince the electorate that they can increase tax revenue without increasing tax rates or bases – it’s the ultimate victimless pledge. However, reducing it is not that simple, evidenced by the tax gap stubbornly remaining at around 5% of total expected tax revenues since 2017-18.

Until now the focus of narrowing the tax gap has very much been on reducing avoidance and evasion. However, these high yield areas are less likely to afford further narrowing of the gap in the future. Instead, the focus should switch to reducing errors and carelessness, particularly across the small business sector. This requires specific investments in HMRC customer service and compliance teams to address these growing problems. This kind of investment in HMRC is unlikely to produce immediate returns in the form of a reduced gap. However, they are vital for the long-term integrity of the tax system, to ensure that it is as easy as possible for taxpayers to get it right the first time.