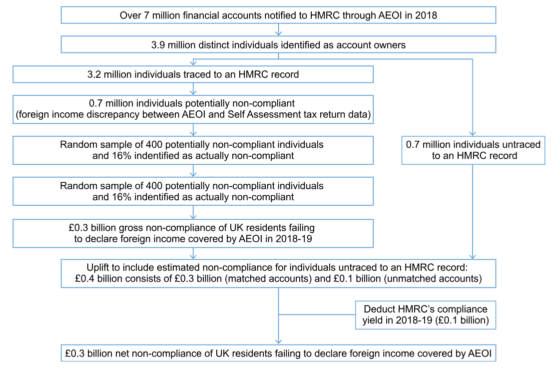

- £300 million tax lost to non compliance by UK resident individuals on offshore accounts in 2018-19

- This figure appears to be a gross underestimate, definitely excluding any assets held through companies, and the treatment of assets within trusts isn’t clear

- 700,000 account holders couldn’t be matched to HMRC Self-Assessment records

- HMRC are extrapolating compliance rates from the tiny (400 case) sample selected for random enquiry process for the entirety of the account holders including those who can’t be found within Self Assessment….

Hurrah, I thought as something resembling the long promised, much delayed offshore tax gap statistics, landed in my inbox this morning (24 October). But the release is deeply misleading.

Getting to something rigorous on offshore assets held by British taxpayers outside the UK and how much tax has been mis-declared or left off the tax returns by beneficial owners of these accounts was always going to be challenging. One of the reasons why the estimate is 6 years out of date relates to the length of time HMRC enquiry and compliance processes take. But is not re-assuring that the statistics are so historic in nature with little sense of how the department will bring down this delay in reporting to be more front footed and proactive with its approach to understanding and then closing the tax gap.

Some significant gaps undermine the usefulness of this disclosure

All offshore assets owned by a company have been excluded. This means transactions between multinational companies, such as intra-group services under transfer pricing rules, and financial assets lent into UK businesses, or used as collateral, don’t feature.

There’s no attempt to account for assets held by UK taxpayers via a corporate wherever in the world the company is located. This is a common route taken and has other (non-tax) advantages e.g. to disguise the ultimate beneficial owner of the accounts held offshore and for money laundering and other financial crime. This is a significant missing component that HMRC just don’t seem to have a strategy of quantifying the revenue loss let alone how to close that gap.

The treatment of assets held by trusts and other structures isn’t clear but based on the methodological annex published alongside the statistics here, it appears that these are similarly been deemed ‘out of scope’. Another big missing factor.

The Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) protocol is far from comprehensive, by the end of 2018 100 jurisdictions undertook their first changes, although it has grown since as the protocol has matured and the quality of the information exchanged has made the data more workable.

Some of the key assumptions HMRC have made in compiling the estimate seem to have been taken with the intention to bring the compliance gap valuation down further.

Extremely small sampling. Seven million accounts held by 3.9 million identifiable individuals were notified to HMRC in 2018. Of the 3.2 million accounts that could be matched to taxpayers filling tax returns, the amounts declared by 700,000 for self assessment didn’t match AEOI disclosures. Only 400 taxpayers of these were selected (apparently at random, rather than attempting to get a balanced sample of territories/account balances/etc) of those who has been subject to a One-To-Many campaign. Within this sample 16% (its unclear to us whether this is by value or volume of the cases) were found to be non compliant. Extrapolating from this small sample is statistically prone to error.

700,000 (a wholly different group from the 700,000 referred to above) individual account holders identified under AEOI disclosures couldn’t be matched to HMRC records (of 3,900,000 total ie 18%). It appears to TaxWatch that HMRC then assume that the on compliance rate established by the narrow sample from an entirely different population (i.e. those taxpayers within Self-assessment and filing returns) is appropriate to use for the group not matched to a Self-assessment record. This seems deeply implausible.

Further to this for any taxpayers not disclosing their income and gains at all the value of the gap should be the entirety of the tax on the undeclared asset, not merely the delta between the two reported figures. Rather than consider the chances that these accounts were more likely to be non-compliant than the sample taken for the other group, or investigate further as to the missing reconciliation, or assume a higher value for each case they have extrapolated the non compliance rate and seemingly used it across the board. This is not a neutral assumption.

Tax gap reporting has always been done after accounting for the yield raised by HMRC compliance activities. TaxWatch has long felt that this is highly questionable for the domestic tax gap, but the methodological issue is much more pronounced for offshore matters and especially taking one year into account, which this first report does.

Are we any the wiser?

Whilst it’s a relief that the wait to see HMRC’s first attempt at an offshore tax gap is at last over the data relates to such an old year and is based on major excluded items and questionable assumptions that the insights it provides are extremely limited. It tells us more about the areas HMRC seem uninformed on than the areas of insight.

It’s a start, but little more.